I recently celebrated my sixtieth birthday. As I have aged I’ve found that milestone birthdays tend to carry with them a propensity for luring me into random episodes of recollection and reflection. It was in just such a state of mind that I found my initial collage of arbitrary memories from the past sixty years begin to coalesce and focus unexpectedly into a single scene. It was a memory from forty-eight years ago, a childhood memory that I had stored away and all but forgotten, as one stores a keepsake in the attic only to rediscover it years later by accident, perhaps as the result of some unrelated life-event – dusted off and rubbed clean on the front of an old t-shirt, suddenly it is fresh and almost new again. And so it was for me as my mind quickly began to wipe off this dusty memory and hold it up to the light. It was the memory of a brief and singular encounter I had with a man named John Gwynn, Jr, who lived in my neighborhood, in my hometown of Peoria, Illinois – an encounter that impacted me at the time in a strange and uncertain way I could not then define. Now, contemplated through the clarity of many years, it has become an encounter the memory of which I treasure, for I fear that its likeness will not be duplicated – at least not in our current society and culture.

There was a day and age, even within my own lifetime, when humility was viewed as a key component of greatness. I am of the opinion that arrogance has supplanted humility in that formula, the outcome of which destines us to the rule of mediocre men. That which follows is a true story about the power of a lost virtue and its effect on the life of a twelve-year-old boy, and a sixty-year-old man.

1969 was a strange year. It was a “between” year, a “wait and see” year, a “what’s going to happen next” year. More than anything it was a “how much worse could it possibly get” year. 1968 had been a duesy – Bobby Kennedy assassinated, Martin Luther King assassinated, tensions over the war in Vietnam at an all-time high, racial tensions at an all-time high, riots in Chicago, heck – riots everywhere. President Johnson declined to run for re-election and Richard Nixon rose from the ashes. The list of bad stuff that happened in 1968 seemed endless. Our country had not been so fractured since the Civil War. In 1970 the Beatles broke up. That’s all that needs to be said about that horrible year. Sandwiched in between was 1969. On January 20, 1969 in Washington, DC, Richard Nixon was inaugurated as the 37th President of the United States. He had promised to fix everything. Voters decided to give him a chance. Two weeks later on February 3 in Peoria, Illinois, I turned twelve years old. My only promise was to myself, and it involved a red bicycle.

While, at the ‘grown-up’ age of twelve I was certainly aware of what was going on in our country and in the world in 1969, I did not care, not in the least. The Beatles were still together and I was busy picturing myself seated in the slick, red banana seat of a shiny new Schwinn Apple Krate bicycle. The Schwinn Krates were eye-catchers: stingray style seat and handlebars, glossy paint jobs, chrome fenders, 5-speed stick shifters, slick rear tire, front drum brakes. One of the kids in my neighborhood had an Orange Krate. As soon as I saw it I knew I had to have one. Mine was going to be the candy-apple red Apple Krate. It would cost me about $110 to ride a Krate out of the local Schwinn bicycle shop. That was an unearthly amount of money in 1969. The kid down the street who had the Orange Krate was the son of a self-employed plumber. In our working-class neighborhood, we considered him a rich kid. For a kid like me, a brand-new Apple Krate was as far out of reach as the moon, except for the fact that I had the ultimate equalizer for poor white kids in the 1960s. I had a paper route.

I will freely admit that my general memories of the paper route years could be slightly skewed. Every image that I am able to recall from my paper carrying days includes at least two feet of snow, howling winds, sub-zero temperatures, and Butternut bread bags tied up over my Red Ball Jets to keep my feet dry. In fact, if one were to use my paper route memories alone as a basis of fact, one would have no choice but to consider the years 1968 through 1971 in Peoria, Illinois, as an incredible climatological anomaly – four solid years of nothing but winter. I’m just telling you what I remember. Managing a daily paper route in the 1960s was hard work.

Every day except Christmas my paper bundles were tossed off the delivery truck at the corner of Bradley Avenue and Rebecca Place. The house in which I grew up, with my six brothers and sisters, was on Rebecca just a block north of the paper drop. Bundles were dropped at that corner for multiple routes so typically there would be three or four of us picking up our papers at the same time and then going our separate ways to deliver our individual routes. We carried the papers in large canvas bags that hung on our shoulders. I started carrying when I was eleven. I don’t mind saying walking a route with those heavy bags stuffed with newspapers gave me an unusually strong back by the time I was twelve. I’m certain newspapers back then, like everything else in the ‘60s, must have contained lead. Most of the time I loaded my bags with the papers still flat and folded them as I walked my route. There was a certain way you could fold or roll the papers so that they would stay rolled when you threw them. You could not get a good solid “thunk” on the front door from a thrown paper that was not tightly rolled.

Once a week all the paperboys in the area had to go meet with the local route supervisor. My route supervisor was a middle-aged guy whose face looked like an old catcher’s mitt with a dried set of lips sewn into the heel. A lit Camel cigarette dangling precariously – and in open defiance of the law of gravity – from the corner of his mouth completed the vintage 1960s look. I don’t remember his name so I’ll just call him Rawlings, like the ball glove. The meeting place was a parking lot. I think ours was a McDonald’s. Rawlings would sit in his car as if on a throne as all the local paperboys rode up on their bikes and hovered around him like loyal subjects awaiting their turn to pay tribute to the king. If this scene were to unfold today it would likely elicit calls to 9-1-1 reporting a child predator in the neighborhood.

Mr. Rawlings would give us any complaints that may have been called in on us and, if we had any new customers, an updated route list. We would, in turn, have to pay our route newspaper bill. This was the newspaper publisher’s little-known secret. When a customer stiffed the newspaper by not paying their bill they really weren’t stiffing the newspaper at all. The newspaper always got its money – the money came from the paperboys. It was the paperboy’s job to collect the customer payments each week. One evening a week I walked my route, collection book in hand, and knocked on each customer’s door collecting their weekly charge for the paper. We paid Mr. Rawlings for the newspapers regardless of whether the customers paid us or not.

Now on most routes this was not a big deal. People happily paid on time. If they missed a week or two they caught it up quickly. However, on my very first paper route, it was a huge deal. Not that my first route was all bad. It had an upside. There were a number of pretty girls from my fourth grade class at St Mark’s Grade School whose homes were on that route. All of their parents paid just fine. My receivables problems were not with the single family dwellings on the route. My problems were with the college students. You see, my route also included every dorm and frat house on the Bradley University campus. There were, at the time, Bradley professors who required their students to get the paper for certain classes. Of course we all know college students are perennially broke and, at Bradley anyway, what money they did have went to beer. Ergo, not paying the paperboy meant (you guessed it) more beer. Ditching the small, shy little four-eyed eleven year old paperboy with his collection book became quite a pastime on campus. I, however, was not one to be taken advantage of for long – especially when it was MY money at stake. I soon developed business strategies designed to cut my losses and mitigate future risks. The seeds of my self-reliant arrogance were beginning to sprout.

My initial attempt at recovering the profitability of the route was simply to tell Rawlings that I wanted to cancel the subscriptions of all my customers that were more than a month behind. They were not paying me therefore they should no longer receive my product. His nice guy smile disappeared long before I could finish my argument. That was not going to happen. According to Rawlings, I was just going to have to work harder at collecting the money. Find a day and time when the kids are in their rooms and not at class. They are good kids. They will pay. Yeah, sure they will. I was amazed at how the cigarette held fast to his lip in spite of all the BS flowing from his mouth. It did not take a genius to understand the simple fact that there was no good reason for the paper to cancel these subscriptions. After all, the newspaper was getting paid. It was getting paid by me. They did not care if I was unable to collect.

This realization led me to a remarkably more successful approach – a tried and true business tactic that has been around since the dawn of civilization. I lied. I began making up stories designed to get Rawlings to cancel subscriptions on my delinquent accounts. One story had the student moving back home because his mom died. Another involved a student flunking out. Still another fabrication had a student dropping out to join the army. (Considering what was going on in Vietnam at the time, I didn’t really think that one through from the credibility angle but it worked nonetheless). All of these stories worked. I am convinced that most people would rather believe in a lie they like than face a truth they dislike. Rawlings proved to be no exception. Even after the papers were canceled and I had cut my losses I continued my collection attempts for amounts still owed. If I hit on one, it was clear profit. If not, I was out nothing. I had become a savvy eleven-year-old debt collector.

Luke 18:9-14 gives us the record of Jesus’ parable of the Pharisee and the publican (tax collector) praying in the temple. Luke begins the account in verse nine with this statement – “To some who were confident in their own righteousness and looked down on everyone else, Jesus told this parable” (italics mine). In the margin of my Bible next to this passage I have written these words – “contempt for others is the fruit of a prideful heart”. It was a fraternity boy named Gallagher who gave me my first taste of contempt born of pride.

Gallagher’s frat house was located on a street called Fredonia. I don’t remember the name of the house – Phi Sigma Chugga Coors, or something like that, but I’m pretty sure I would recognize it if I drove past it today. I knocked on that front door so many times the image of it is stuck in my head – big red double doors, small cement porch, and the requisite snow piled on the threshold and on the sidewalk leading up to it. Gallager was a piece of work. Somehow, no matter what time or day of the week I would show up, his buddies would tell me that I had “just missed him.” The “just missed him” story was enough to keep me from coming up with a lie to cancel his paper – not that I believed that I had truly just missed him, but because most of my deadbeat college students were ghosts whom I never saw, and no one I spoke to had ever heard of them. At least Gallager was a real dude whom people knew and told lies about to protect. By the time Gallager had fallen two months behind I decided that knocking on the front door of the Chugga Coors house was no longer sufficient. I would need to go in and find him.

It was a frigid winter evening. I strode up the sidewalk to the Chugga Coors front porch and, with adrenaline pumping, grabbed the door handle and waltzed in like I owned the place. I was so nervous my senses went into overload. The moment I stepped through the door I felt like Frodo the first time he put on the ring. Everything around me was a wavy, shadowy shade of gray. As I looked around the room and got my bearings I saw a guy and a girl sitting arm in arm on the bottom step of a staircase. They were both looking at me with raised-eyebrow smiles on their faces. “I’m looking for Gallager,” I said, channeling Joe Friday and flashing my paperboy collection book as if it were a badge. The guy didn’t say a word, just pointed up the stairs and smiled at me in a way that made me feel more like Alfalfa than Jack Webb. It was not the impression I had hoped to make. I did my best to gracefully step around him and his girl as I skittered up the steps.

The staircase terminated with a large room on the right and a short hallway on the left. The room contained five or six frat boys, each of whom immediately turned to stare at me as I reached the top landing. I saw some smiling eyes, I saw some angry eyes, and I saw at least one set of downright astounded eyes. Quickly acclimating now to my new tough guy persona, I flashed my badge at the staring eyeballs and spoke one word – “Gallager.”

One of the sets of smiling eyes pointed toward the hall. “Shower,” he replied.

I turned to my left and walked toward the hall. I could feel myself being followed. The hall led to a large bathroom/shower area. There was one fellow standing in front of a sink, with a towel around his waist, brushing his teeth. I heard the sound of a running shower behind him and to his right. Now that I had come this far I really did not know what to do except to accomplish my mission. I won’t lie. I was scared. I decided I was going to have to be as bold as the one-eyed fat man in True Grit. I approached the stall that appeared to be the source of the running water sound – the only one that had the shower curtain pulled shut. I felt eyes drilling into the back of my neck. I had crossed the Rubicon – there was no turning back. Grabbing the curtain with my right hand, I pulled it open while simultaneously flashing my badge with my left hand. Making a point to maintain my gaze above waist level, I announced with a loud voice: “COLLECT.”

Gallager didn’t know what hit him.

The ensuing spectacle remains a bit of a blur in my memory. There was too much going on in my head to fully process it all. I remember an explosion of laughter, some applause, some loud chiding, even a few pats on the back. Through it all I managed to keep my gaze above waist level and to maintain my stony, bill collector face. Yet, on the inside I was doing cartwheels. I felt somehow superior to this naked frat boy, and it felt good. No, it felt GREAT. Throughout my school years to that point I had been the living stereotype of the kid that had “pick on me” written on his forehead – small, timid, thick glasses, socially awkward, different. My favorite pastime was reading the encyclopedia, for crying out loud. Getting one over on this guy, the pats on the back, the applause – it was all new and exhilarating. Looking down on other people was what the cool kids did. I knew because they did it to me. Now I understood the attraction. The apostle John calls it “the boastful pride of life” I John 2:16 NASB.

Eventually Gallager recovered, dried off, dressed, and got me my money – every penny of it. I want to say it was six or eight dollars and some change. I can’t really recall. What I do remember are the looks I was getting from some of the frat boys as I made it a point not to smile or join in the frivolity. For me, this was serious business. Dude owed me money. My stoic nature would not allow my conceit to betray itself in celebration. A few of the college boys had begun looking at me with what I perceived as a degree trepidation in their eyes. Was there a reason for this kid’s boldness? Was he connected and protected? Most of Bradley’s student population was from the Chicago area. They knew what it meant to be connected. The fact is, all of my initial boldness that day was rooted in the fact that I was connected. My bodyguard was standing on the sidewalk in front of the house waiting for me.

I walked out of the Chugga Coors frat house and toward the shadowy figure waiting near the street. “Well?” came the voice from the shadow.

“Got it,” I replied.

“Goodt,” my mother said, betraying a hint of an accent as we walked to the next stop on my collect list.

You see, my mom always went out with me when I did collections at night. I would be carrying a fair amount of cash and she worried about me getting mugged. My mom is German – 100%, grew-up-in-a German-speaking-home German. Not only is she German, but back then she had a temper and she knew how to use it. For a kid raised on WWII television shows like “Combat!” and “The Rat Patrol”, being German held a fearsome mystique. I felt certain my mother could have any aspiring mugger screaming uncle faster than you could say blitzkrieg. If need be, she could have the toughest frat boy at Chugga house surrendering like France. It was a heritage that I took pride in, adding all the more to my new-found swagger.

Early in 1969, sometime around my birthday, Mr. Rawlings offered me the opportunity to trade my now-somewhat profitable route for a much larger and much more profitable route right in my own neighborhood. In fact, it included my own house. I jumped on it. This was perfect. More money meant a shorter timeline to $110 in the bank. Fewer college students meant less collection problems. Proximity meant I could finish the route right at my front door instead of having to walk several blocks to get home once my papers were delivered. I was on paperboy easy street and I felt I deserved it. My mom was happy also. She was much more comfortable with a twelve year old collecting money in our own neighborhood than with an eleven year old roaming around neighborhoods a mile from the house. In 1969 my mother officially retired as my enforcer.

Things went smoothly on my new route. As an experienced paperboy, I knew how to keep my customers happy and complaint-free. This, in turn, kept Rawlings happy. Collections were very smooth. There was only one house at which I never seemed to be able to find anyone home. It was on Cooper Street – just a block to the east of my house and about a half-block to the north, between Laura and Main on the east side of the street as I recall. The name on the account was John H Gwynn, Jr. Mr. Gwynn’s account quickly fell over two months past due without my ever having laid eyes on anyone in the home. No worries, eventually I would find someone home and get the account caught up. That is how it always worked with homeowners in our white working-class neighborhood – good people, salt of the earth, all that jazz. It was somewhere around that time when I mentioned the man’s name to my dad. I was surprised that my dad knew who he was and that Mr. Gwynn was somewhat of a local celebrity. It was at this point that I became aware that the Gwynn family on Cooper Street was black. John Gwynn, Jr. was the head of the Peoria chapter of the NAACP.

I recall getting the distinct impression from my father that he was no fan of Mr. John Gwynn. He was not a hater by any means, just not a fan. It was not that my dad was a bigot. I saw too much evidence to the contrary to ever believe that to be true. Dad did, however, hold to what I would describe as the typical northern white working class mindset of the 1960s: the idea that the struggles of the white working man were indistinguishable from those of the black man in America. In other words, “What are you guys complaining about? We don’t have it any better than you do!” It was a false perception of racial equality that was not true in 1969 and, speaking from first-hand experience, I can say that it still persists and is still untrue today in many blue-collar work environments in the region of southwest Missouri that I currently call home.

This brand of racial tension was typical of what I recall from my small corner of the world in 1969. It was not a tension fueled by hatred. Prejudice fueled by hatred is a self-evident and undeniable malignancy. That was the type of racial prejudice that we heard and read about from the Deep South. I never saw or experienced anything of that nature during my childhood in Peoria. What I did see, the type of racial tension I recall, was much more subtle, and perhaps even more durable. It was a tension fueled by isolation, by ignorance, by a stubborn attachment to untruths perceived as fact. It is an attitude that says – “if I do not experience the problem myself there is no problem”. People do not like to set aside those things that they desire to be true. Falsehoods encased in the mighty stronghold of self-righteous assurance are difficult to break asunder. Therein lies a vast gulf fixed between two opposing sides.

Though my twelve-year-old mind was not occupied with such complex thoughts in the late winter of 1969, my bias was certainly set to bear them out. My conscious mind was set on attaining a red bicycle and on what I now perceived as a major obstacle to its purchase – one John H Gwynn, Jr, president of the Peoria NAACP. This man was no longer a faceless name on a delinquent customer list. My experience had taught me that faceless homeowners always paid up eventually. They did not concern me. I’ve already related my issues with college students but this man was not a student, either. This was a different entity altogether. For one thing, he was a celebrity. Old catcher’s mitt face would never cancel this guy’s subscription. That meant he could decide not to pay me for the rest of my paperboy working days and there was not a darn thing I could do about it. I soon convinced myself that this, indeed, was Mr. Gwynn’s intention. After all, he was a rabble-rouser and a troublemaker. The other kids in the neighborhood had heard their own parents talking about Mr. John Gwynn. They all concurred. The guy was bad news.

After a few more weeks of nonpayment and no answers at the door, I was convinced. The man was a deadbeat out to steal my money. Admittedly, I could have come up with some alternate collection strategies to try to clear the account and prove myself wrong about the man. I could have left a note on the door with my phone number. I could have shown up to collect at a different time of day than what had always been my norm. I could have done a lot of things, but I did not. It was much more satisfying to simply be “right” about what kind of man he was than to consider the possibility that I might be wrong.

In 1969, if my memory is correct, the cost of the daily Peoria Journal Star newspaper was 10 cents. The Sunday paper was 25 cents. That meant I collected 85 cents per week from my customers who got the paper every day, which most did. Again, my memory may be off, but I want to say by spring of that year the Gwynn account was $12.75 in arrears – over three months. Now that was a lot of money back then, nearly 12% of the total funds I needed to purchase my dream bicycle. I had, in the past, gone to great extremes to collect lesser amounts. So far on the Gwynn account I had done little more than gripe since the revelation of who he was. It made me somehow feel superior and grown up to be able to complain about a public figure and actually have solid evidence and real-life experience to back up my opinion. I had become a real man of the world.

“Why don’t you go over there right now?” The words from my mother on a cool, springtime Saturday morning hit me like a bucket of cold water. I had made the mistake of bragging to her about John Gwynn owing me money. Expecting a response akin to one adult conversing with another, I instead received the one thing an arrogant twelve-year-old boy would never deign to seek – advice from Mom.

“What? Why in the world would I do that? He is never going to pay me,” was my off-balance response.

“I don’t believe that,” she said. “He is a busy man and he probably has a night job. People like that are hard to catch at home. I’m sure he has no idea he’s that far behind on the paper. You have not tried hard enough to collect this one.”

She had me on the ropes but I fought back, attacking the weakest point of her argument. “Night job? What do you mean, night job? He’s the NAACP guy. That’s not a night job.”

“Tim, people don’t get paid for jobs like that, not much anyway. He has a regular job somewhere and he has a family to take care of. They are no different than us.”

I could tell by the stubborn glare on her face as she wiped down the kitchen table that our conversation was over. I would just have to prove her wrong. I snatched my collection book off the counter in the dining room, ran outside, and jumped on my bike.

The ride to Cooper Street was cold. I had forgotten to grab a jacket. No matter – I knew this would not take long. My old bicycle rattled and shook as I rounded the corner from Laura Street onto Cooper. I think I had paid five dollars for it at a used bike shop. For a moment I imagined myself flying around that corner on a shiny new red Apple Krate. Anger quickly exploded those thoughts as I rode up to the front porch of the man who was standing in the way of my dream. The Gwynn house was like any other house on the block: big and old, probably draughty, front porch steps of brick and crumbling cement. Like most of the houses in this old neighborhood there was probably a sealed-up coal chute to the basement around back or on the driveway side of the house. Sounds from both inside and out passed through these houses effortlessly. When you stepped onto the front porch you could generally hear immediately whether or not someone was home. They likewise could hear you long before they heard a knock.

My senses sharpened as I bounded onto the front porch. Someone was home. My short knock was answered immediately. The door swung open slowly from my right to my left revealing a dark, unlit living room. In the foreground holding the door open but standing slightly to the side was an average-sized man, a black man. He appeared to be wearing a wrinkled white t-shirt and an old pair of pants that may have been dress slacks in some earlier incarnation. Standing about ten feet behind him and facing the door was the figure of a woman in a loose-fitting dress. Her face was dark and in the dim room it was hard to make out her features. I could, however, clearly see the features of the man standing in front of me. I was almost startled by how closely he resembled the black and white images on the television and in the newspaper. It was Mr. John Gwynn himself.

The expression on John Gwynn’s face was one of surprise tempered with curiosity. His eyes were piercing but friendly, his closed-lip smile unassuming. He allowed me to speak first. “Collect,” I said in as firm and professional voice as I could muster. I quickly flashed my collection receipt book. I had initially been caught off-guard at finding someone home. I tried rapidly to recover. I had my game face on but inside my heart was beating faster than a baseball card in bicycle spokes. This was not a normal collection call. I had built this man up into such a monster in my head that I fully expected him to get angry, to refuse to pay, maybe even to throw me off the porch. I had dealt triumphantly with all of these scenarios in my mind, but in my mind I was Capt. Kirk. Now it was real life and my enforcer was at home in the kitchen.

A quiet voice responded, “How much do I owe you, son?’ The tone of the voice was deep, almost reassuring.

I could feel my swagger returning. I stared at my receipt book as if I were calculating the bill. I did not need to calculate it. I knew exactly how much it was. “Twelve dollars and seventy-five cents,” I said without looking up. Then, for added effect, I settled my eyes not on Mr. Gwynn but on the female figure standing behind him. “You’re fifteen weeks behind,” I said boldly.

John Gwynn’s eyes got wide. He looked at his wife. There almost appeared to be a look of fear in her face. He turned back to me. “How, how much is it?” he said. “I don’t understand. How did we get this far behind? Why did you not come by sooner?”

I explained, in my most innocent cherub-like voice, that I came by once a week but no one ever answered the door. I did not disclose to him that I had intentionally not left a note or tried to come around at a different time or that the only reason I was there on a Saturday was because my mom made me do it. I braced myself for him to ask me those questions but he never did. At the time I assumed he just did not think of them. Today I am certain he did think of them and simply chose to let it go.

“I work nights. I’m probably asleep when you come by,” he said quietly. Mr. and Mrs. Gwynn left the front door open and disappeared into the house. They were visibly shaken, just a little bit anyway.

I heard drawers opening. I heard the jangle of change and the light sound of closet doors open and close. It dawned on me that if someone had shown up at our house wanting $12.75 cash, I don’t think my parents could have scraped it together. There were a lot of days Mom had to borrow money from me to go get a gallon of milk. That is just the way things were and still are for regular people.

After several minutes Mr. Gwynn reappeared at the door. He had a handful of loose change and a few bills. “I have six dollars and fifty cents. Can you take that today and give me a week to get you the rest?” He spoke quietly, almost inaudibly.

I had not anticipated a counteroffer. Instinct possessed me and I went in for the kill. “I need it all today or the paper will cancel your subscription.” I intentionally crafted my lie not only to deflect blame but to back my adversary into a corner. This was a man who was in the media spotlight. GWYNN SUBSCRIPTION CANCELED FOR NONPAYMENT. I knew he would not want to read that headline. I compressed my lips in a self-satisfied smile, making no attempt to conceal my disdain.

John Gwynn’s lips tightened. He exhaled audibly. I became aware of what appeared to be children in the darkened living room. Mrs. Gwynn was whispering to them and they left the room. Mr. Gwynn walked away from the door without a word and appeared to speak briefly to his wife. Then they, too, left the room. When John Gwynn returned to the door, he held a few bills in one hand and a mountain of change cupped into his other hand. His large brown hands began transferring the funds into my much smaller white hands. Maintaining his soft-spoken voice, he counted the money out as he passed it to me, pausing briefly once so I could empty a handful of change into my pants pocket and reload. His count reached twelve dollars and seventy-five cents. I pocketed the second load of change along with a few bills and tore off fifteen past due payment receipts. “Thank you,” I said as I handed the receipts over. Turning to walk off the porch I glanced back at the man who had been my nemesis. His face held the identical expression I had seen when I first arrived. His eyes were still friendly. His lips still formed a smile. I hopped my bike and headed home.

My ride home was slow and deliberate. I tried to process what had just taken place. I should have felt exuberant and happy. I did not. I should have felt victorious. I did not. I was not sure what I felt. Unsettled? Perhaps. Shaken? Maybe that, too. John Gwynn, Jr, should have responded to me with anger. He should have been combative. The contempt in which I held him could not have been hidden from one who was so accustomed to seeing it manifested in the white man’s world that he was trying to change. He should have told this little punk white kid to get the heck off his front porch. Instead there was a quality in his demeanor that I did not understand and would not understand for many years. I only knew that he was no longer my enemy, and somehow that conversion had changed me.

I never again saw or spoke with Mr. Gwynn. He continued receiving the paper and I continued delivering it, but I no longer had to stop there to collect. The Gwynns had quickly changed their account to a pay-in-office, or PIO, status. That meant they went downtown and paid the paper directly and in advance. I’m sure he wanted to avoid any possibility of once more falling behind.

Later that year, with the help of John Gwynn’s $12.75, I got my brand new Schwinn Apple Krate bicycle, just like I had promised myself. It was pretty and shiny and rode like a dream. But, as much as I tried to make the experience of ownership live up to the dream, it never did. There was something anti-climactic about the whole thing. It was not that the bike had changed and become less than what it was. The bike was no different than I expected. I was different. My priorities had changed. I was searching – searching for something I could not identify. I had not yet found it, but I knew what it was not. It was not ownership of a brand new Schwinn Apple Krate bicycle. Whatever it was I was looking for, I could not easily escape the notion that my search had begun on that front porch on Cooper Street.

Forty-eight years have passed since that cool spring day in 1969. Looking back I can now see that, like all young men from the dawn of history, I was beginning the search for my place in the world. There would be much yet to discover and experience, and to a great extent I am still searching. Life moves on and events from our childhood fade into a shadowy, misty limbo of disconnected memories requiring some sort of catalyst to bring them back to life. In this case the reviving stimulus could have been our current political climate, or the apparent absence of personal integrity amongst our leaders, or maybe the distressing hatred that has found a new means of expression in our social media. Or it could have been my own increased consciousness of the appalling ignorance of a national culture that craves entertainment like a drug and renders truth irrelevant. In all likelihood, it was a combination of all of these elements that drove this lost memory to the surface of my mind on my sixtieth birthday like a saturating rain brings up the earthworms.

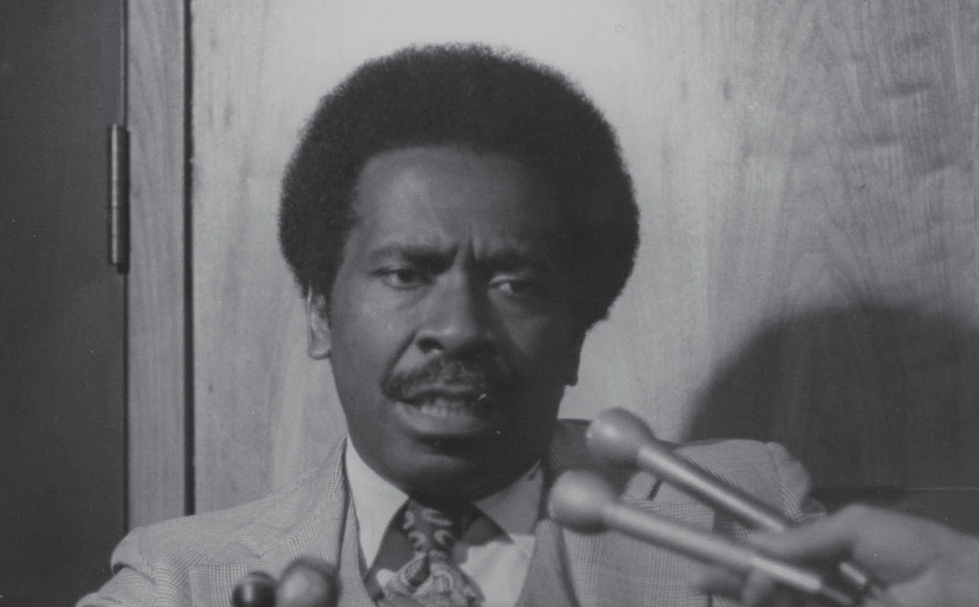

Whatever the reviving impetus may have been, the facet of this recollection that clearly stands in bold relief against our current societal background is the incredible humility displayed by Mr. Gwynn on that day in 1969, and the power a humble response can bring to bear on the issues that separate us. John Gwynn later became the head of the NAACP for the entire state of Illinois. In my hometown there is a street named after him. He was the driving force for racial equality in Peoria through the turbulent Sixties and beyond. And, he accomplished these goals peacefully, with dignity and respect for others.

This attitude, which seems to have vanished even in professing Christendom today, was best described by the apostle Paul: “Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit. Rather, in humility value others above yourselves,” (Philippians 2:3 NIV) Hear that again – “value others above yourselves”! I think about that often.

Speaking of Christ, Paul wrote that He “…made himself of no reputation and took upon him the form of a servant, and was made in the likeness of men: And being found in fashion as a man, he humbled himself…” (Philippians 2:7-8a KJV) The phrase “made himself of no reputation” is the KJV translation of the Greek eauton ekenosen – literally: “he emptied himself”. Of what did He empty Himself? I believe one can make a strong case that the “kenosis” or emptying of Christ was primarily an emptying of self-reliance. Jesus is God of very God and yet in His earthly life He relied completely on the Father in all things. He emptied Himself of self-reliance. Reliance upon God is the essence of humility. While the KJV rendering is not a very accurate translation it is an excellent paraphrase of the full sense of the Greek – He made Himself of no reputation! He made nothing of Himself! God of very God and He made nothing of Himself but relied fully on the Father for all things. Who amongst us can even come close to saying that?

My paper route experiences had taught me self-reliance at an early age. I had built my self-reliant fortress on a foundation of superiority, arrogance, and pride. Our society values self-reliance. It is one of the primary traits we try to instill in our young men. One of the most common ways that we manifest this sovereignty of self is to buy “stuff”, to attain the things we desire. My growing autonomy had turned a red bicycle into the desire of my heart. John Gwynn did not destroy my fortress. I’m not sure that he even shook the foundation. What he did was more akin to an acorn taking root in a tiny crevasse in the wall. A small thing at first, but over time…

Although I only interacted with Mr. Gwynn on this one occasion, it seems evident from the testimony of others who knew and worked with him that his powerful leadership philosophy was firmly anchored to the core values of humility and selfless service to others. I believe his example truly demonstrates the universality of the power of a humble spirit. Self-reliant men may achieve success. Humble men achieve greatness. The nineteenth-century British social thinker John Ruskin said, “I believe the first test of a truly great man is in his humility.”

As for me, I can at least personally attest to this – the humble response tendered by this one man contained within it a power dynamic enough to build a bridge over the vast gulf that separated a peaceful 1960s black activist and the arrogant white kid who had vilified him. It was a bridge, the construction of which was not initiated from opposing sides and completed in the middle. Rather, it was a span erected from one side only, start to finish. And it has held, even to this day.

POSTSCRIPT –

John H. Gwynn, Jr (1929 – 1996) was the voice for racial equality and civil rights in Central Illinois throughout the turbulent decade of the Sixties and well beyond. He was president of the Peoria chapter of the NAACP for 32 years from 1961 to 1993. In his book ‘Legendary Locals of Peoria Illinois,’ author Greg Wahl describes Gwynn’s courageous attitude and intense commitment:

His rousing 32-year stint shook River City to its core. He was an assertive president and defied city leaders who shied away from racial problems. He knew civil rights needed to jolt the establishment in order for real advancement to be made. He saw a 1950s – 1960s Peoria that denied its de facto segregation and rammed that unpleasant reality home. Though mild-mannered by nature, Gwynn would meet injustice with ferocity; those who looked into his eyes couldn’t deny the intensity of his commitment to civil rights. His dedication would lead to throttling discrimination in Peoria housing, local government, schools, restaurants, unions, and in workplaces such as Caterpillar and utility companies. At times he found himself jailed, a small price he gladly paid for his cause.

One man who worked with Gwynn in the NAACP said of him:

He was the closest thing to a jesus. He didn’t want no materialistic things. He worked, and spent all day trying to right the wrongs.

Another man who, as a young boy, participated in some of John Gwynn’s organized boycotts recalled this encounter:

He told me to stand up and be proud of my heritage and look men straight in the face and answer him like you had integrity in your life, not like you were a thug or hoodlum but as a man.

Considering the enormous positive impact that Mr. Gwynn’s life had on behalf of the working men and women of Central Illinois, I was somewhat shocked at how difficult it was to uncover even the most basic biographic information on the internet. That saddens me. Many men of far less accomplishment have found their way onto the virtual pages of Wikipedia. I hope my story helps in a small way to correct this disservice to his legacy, although I expect that a man of Mr Gwynn’s nature and demeanor would think it just fine to remain an individual of no reputation. “After all,” I can imagine him saying, “it was the work that was important.”

Leave a comment